- The challenges of bringing professional telescopes to life

- How astronomy helps us collaborate with each other and understand what's around us

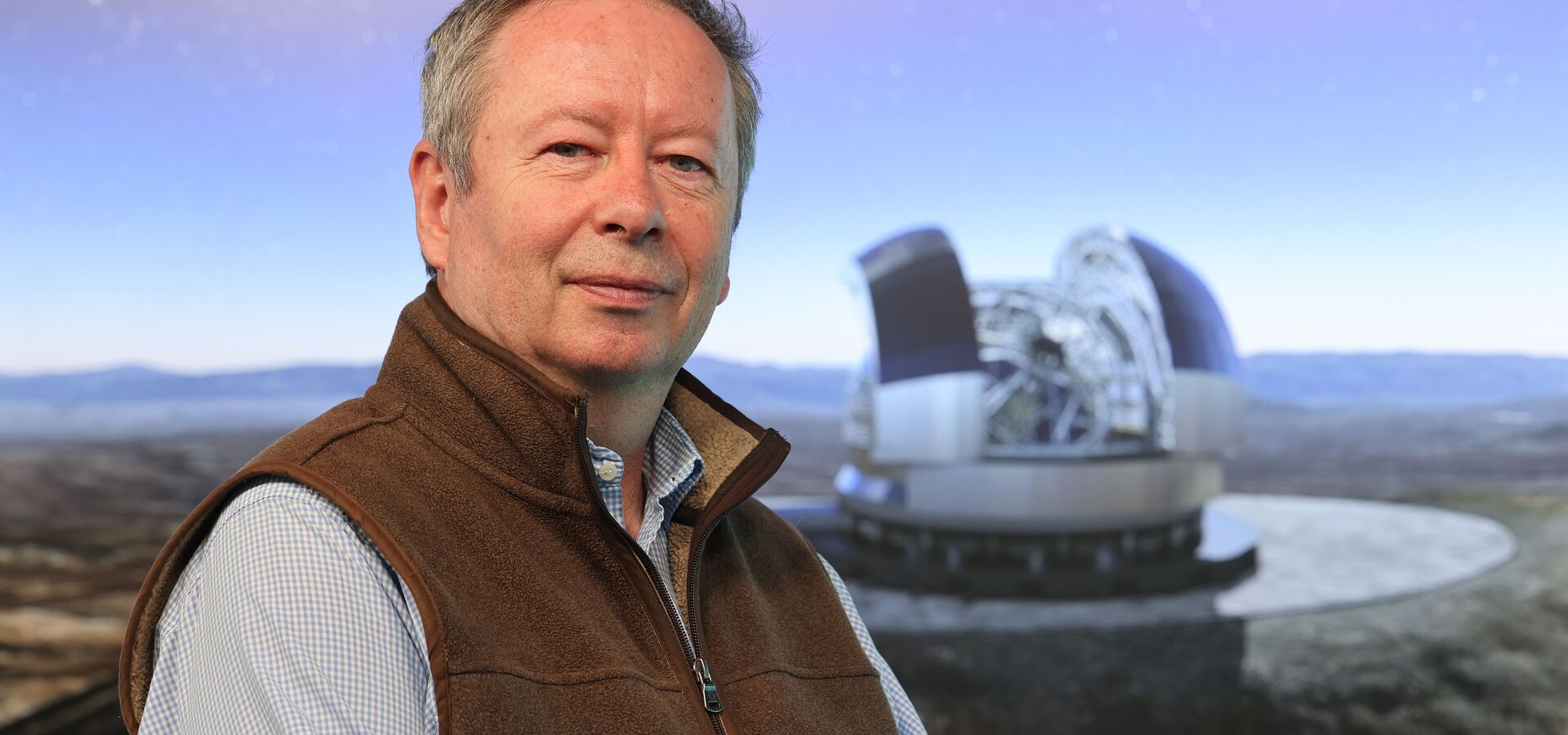

Bertrand Koehler held his first telescope at age 13. Under a summer sky, at the home of his best friend in Normandy, he remembers well the craters etched into the Moon and the rings of Saturn through a small, refractor.

“It was absolutely marvelous,” he recalls, from his office at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Germany. “I had the impression that I was flying over the Moon. I hadn't imagined we could see the craters so well. And Saturn's rings looked just like a cosmic jewel.”

Bertrand, now two years from retirement, has come a long way from his summer nights of stargazing in France. He has traded the starry skies of Normandy for the busy streets of Munich, and upgraded the 9 cm refractor to something much, much larger: Bertrand is directly supporting the Program Manager of ESO's upcoming Extremely Large Telescope ( ELT ), the largest optical telescope in construction. The ELT will be a massive 39 m in diameter.

But Bertrand, who will leave ESO before the ELT first opens his eye to the cosmos, is not focused on just building a telescope: “Ultimately, my motivation for being here is not to be an engineer,” he emphasizes, “but to work for astronomy. I think that's something which is very important for mankind.” And while the ELT is Bertrand's big project of today, the crown jewel of his career, for him, lies in the Very Large Telescope Interferometer ( VLTI ), and the four Auxiliary Telescopes that came with it.

“It was a personal, exciting, and challenging experience. But it was also hard work, taking much of my attention, even often outside work.”

In the midst of camping in the Chilean desert, court orders on Paranal, and helpful truck drivers, Bertrand's journey to see the first light of the VLTI answers a question he never needed to ask: why care about astronomy?

“I'm really happy to have spent all my professional life on it,” he says. “What we do here is for a purpose — for increasing our understanding of the universe, and raising our global consciousness as human beings.”

Part I: The Road to the VLTI

After his first contact with a telescope as a child, Bertrand’s future career in astronomy — and to eventually be observing the first light of the VLTI — had been inevitable. “My parents bought me a small telescope, and I started to observe,” he says. “I was trying to do what Galileo had been doing: making some drawings of the satellites of Jupiter from one day to the other, and trying to see if I could compute the orbits, and things like that.”

Later, Bertrand pursued a Masters in Astronomy in parallel to studying Space Engineering in Toulouse. “I decided that with my engineering degree I would be more flexible to find a job in different places, because I was also from very early on interested in various cultures and languages.”

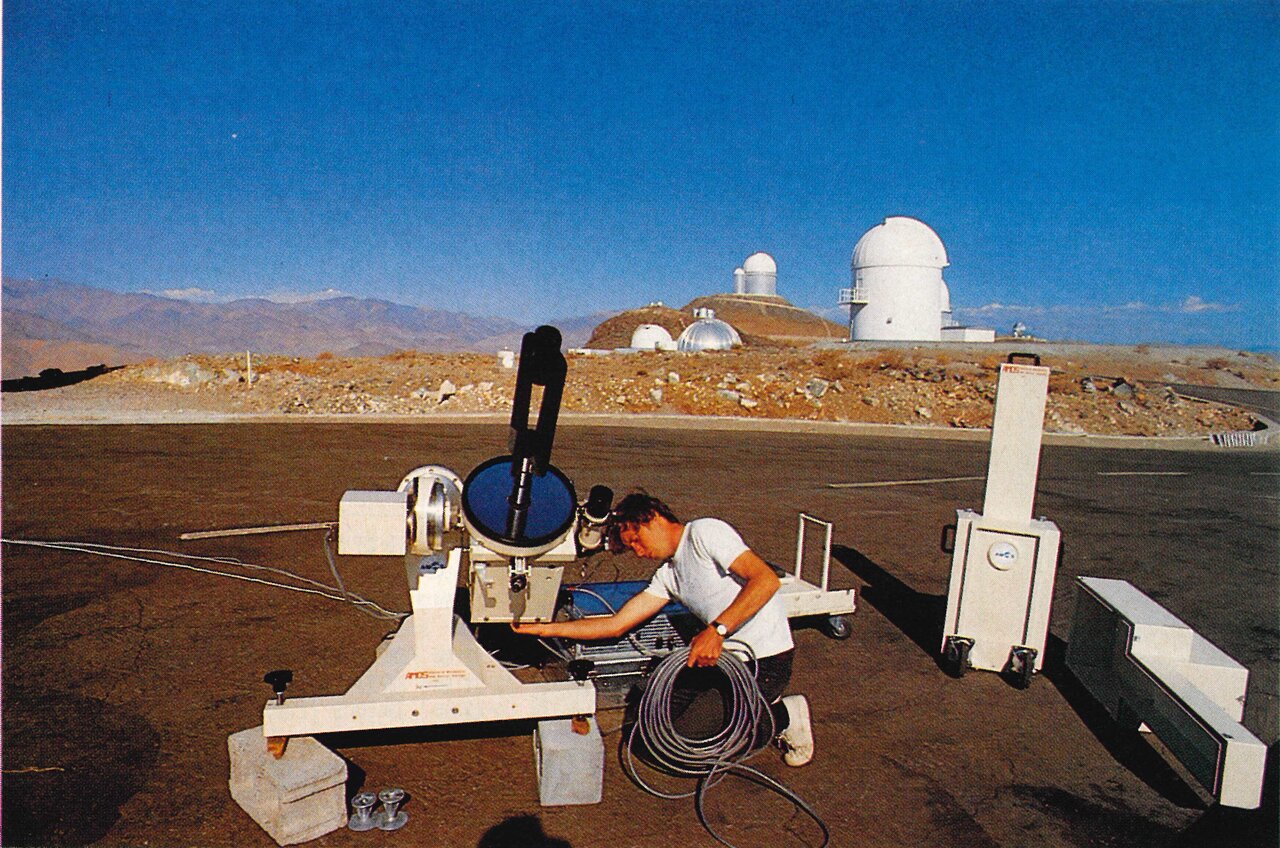

In the early days of his career, Bertrand ventured out of France and across the globe, to a remote, lonely place in the dry heat of the Chilean desert: the La Silla Observatory. “I wanted to have an experience abroad. We helped astronomers prepare their observations, when everything was still pretty much manual.”

La Silla was ESO’s first observatory, sitting in the remote edges of the Atacama Desert under some of the darkest skies in the world, and surrounded by the mountains and volcanoes of Chile. For Bertrand, it was a gateway to adventure. “I found this place fantastic. I really travelled in Chile a lot, from South to North, and also did a lot of mountaineering. The highest was the Ojos del Salado, which is about 6900 metres!”

Meanwhile, ESO had been devising a ground-breaking telescope: one with unprecedented resolution, that would change the landscape of astronomy. Having cracked the code of active optics with the New Technology Telescope (NTT), the telescopes were freed from the “small” 4m-ish mirror sizes that had bound their previous constructions. ESO’s telescope of the future would be Very Large — but where to put it?

Telescopes thrive at high altitudes. For many, travelling to the driest, loneliest corners of the desert would be a chore, but not for Bertrand. “I’ve always been doing a lot of mountaineering, being in nature, sleeping outside without a tent… My involvement in the site testing was, for me, also an adventure.” Cerro Paranal, a mountain in the northern Atacama Desert, was eventually chosen to be ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) home.

After 18 months, his service in Chile coming to a close, Bertrand returned to France to work as an engineer at Aérospatiale, a large aerospace corporation. This was an opportunity to learn about the high-tech industry — but Bertrand also had other motives.

“They were also working on the feasibility study for the secondary mirror of the VLT,” Bertrand says, “and I thought, ‘I can keep contact with this institute.’ After three and a half years there, I applied for a position for the VLTI, and I came to Munich in 1991 as a system engineer.”

Part II - ‘Are you crazy?’

Bertrand Koehler arrived in Germany in July 1991, leaving the glittering blue waters of the Côte d'Azur behind him in pursuit of the VLTI. “My colleagues were saying, ‘What, you will go to Germany? Are you crazy? You are here in paradise on Earth!’” he recalls.

Bertrand was now a part of the uphill battle to create an interferometer of impressive size. “Interferometry had been done here in Europe on only a very small telescope, 20 centimetres — not with 8 metres,” referring to the main mirrors of the VLT.

Interferometry is a clever trick for astronomical observations: by linking the observations of two or more telescopes, astronomers create a ‘virtual telescope’ with readings as detailed as though they were taken with a single, immense telescope with a mirror as big as the distance between them. The Very Large Telescope would really be four very large telescopes, which could either be used independently, as the VLT, or together, as the VLT Interferometer (VLTI). But interferometry at this size was unprecedented.

Bertrand also became the project lead for the four additional 1.8 m telescopes (known as Auxiliary Telescopes) that would be able to move around, setting the distance between them exactly as needed for each observation. This would allow for full-time use of the VLTI infrastructure, even when the 8 m Unit Telescopes were being used for standalone observations.

But this required an unprecedented stability. “I remember when I arrived — you know, the young engineer — and some were saying, ‘It will never work, it's hopeless, you want to achieve the stability of nanometer dynamic vibrations, it's impossible!’ But I was challenged by that.”

His biggest obstacle: the construction site of Paranal Observatory, where the VLT would one day live. “I realised that earthquakes occur almost continuously — small ones — and the VLTI is extremely sensitive to vibration. I was wondering: ‘Aren’t we going to be disturbed every night with a smaller earthquake, which would [...] degrade the signal?’”

The question sent Bertrand back to the deserts of Chile, on a mission to measure even the smallest of vibrations of the mountain landscape. Unfortunately, Paranal was the opposite of serene; a cacophony of machinery and controlled detonations to shape the mountain top.

“I wasn’t sure we’d be able to measure,” says Bertrand. “We’d have to wait for the night, when there is nobody around.” But the very day he arrived, a car pulled up the dusty road to the VLT.

“A judge came down from the city and asked to stop the VLT work. A family had claimed they were the owner of the ground,” Bertrand recalls. “Thanks to that, the activity stopped for exactly the two weeks I needed to do my measurements.” Laughing, he adds, “In the unluck of ESO, I was lucky for my own purpose!”

While this legal tangle was untied in the background, Bertrand’s seismic measurement campaign stuttered, as they found they needed a heavy weight, but there was nothing suitable available at Paranal. “This was a time when there was literally nothing on site — no workshop, no tools, just heavy civil work with dynamite and excavators. We were desperate, about to declare our campaign failed, when this Chilean water-truck driver got the solution for us!”

The Atacama desert, where Paranal is located, is one of the driest places in the world. This makes it an ideal site for astronomy, but also makes dust breezes a real issue. The land would therefore be sprayed down with trucks of water to tether the dust to the floor — it was pure luck that one of these trucks would be passing by, with a quick-thinking driver at the wheel.

“He kindly sawed a heavy metal bar off of his truck to help us. I could not believe it! But a very practical way of solving problems is in fact a must if you want to survive in such a severe desert environment. This is a good example of the strength of combining different cultural ways of working.”

Finally, in 2001, the VLTI had its first light. “Of course, getting the first fringes from the VLTI is something that stays in my memory,” he says. Fringes are the interference patterns resulting when the beams from different telescopes are combined. “We got them on Sirius because it was bright and relatively close to the zenith. But the same night, we tried to look at another star, and we didn’t find it!”

“Then the next day, the same. We were starting to be a bit worried.” Bertrand had the idea to track Sirius for long enough to work backwards, and check the orientation of the VLT telescopes. “We realised that the whole platform was rotated by 0.6 degrees, with respect to the theoretical value. Not much, but in astronomy, we look for small angles.”

The fix was, luckily, an easy one, achieved by adjusting some numbers in the software. Following celebrations in the Control Room, the VLTI shot into action.

Part III - ‘How lucky we are to be on the Earth…’

A few years after the VLTI found its first fringes, the four auxiliary telescopes each had their own first lights, starting from 2004. “I delivered four Auxiliary Telescopes to the Paranal observatory — and it felt like having had four babies!” Bertrand says.

“The feeling to have been the one behind this development — of course with the invaluable support of excellent colleagues and the industry — from its conception (the first feasibility studies), through its birth (placing the contract) until adolescence (the first light and subsequent operation) is really rewarding.”

Meanwhile, the VLTI has returned outstanding scientific achievements — for Bertrand, this is the most important reward for his work.

“It was a big pleasure to see that there has been a significant scientific outcome from the VLTI,” he says. “When I was young, I started talking with my father, who was a more practical industry-engineer, about studying astronomy. I could feel that he was not convinced that astronomy was really useful. I personally think it's very useful — for the development of society, and to increase our awareness of where we are, and of this Universe around us.”

“With astronomy, we understand that it's not so nice to be in the middle of nowhere in a vacuum, or close to a star when it's going supernova. You realize how lucky we are to be on the Earth. It's a way to increase our awareness of our responsibility to take care of our planet, and to work together, rather than make war.”

Now, Bertrand is working on the Extremely Large Telescope, which will bring a new era of scientific discovery — but it is expected to take first light in 2028, after he retires. “I will have to follow it on the internet! Still, my motivation is very vivid, because getting scientific results coming out remains the ultimate motivation for me.”

Bertrand hopes the ELT and future telescopes will continue to inspire. “Galileo showed how astronomy can open our eyes, and our consciousness. I hope we go further in understanding our Universe, and being at peace with ourselves.”

“I think it's the most fascinating thing in life: to feel that you are more and more aware of what is around you. For me, astronomy moves us in that direction.”

Links

- The VLTI first light parts 1 and 2 .

- VLTI First Fringes with Two Auxiliary Telescopes at Paranal: press release & video .

Biography Louisa Spillman

Louisa is originally from a small countryside town in England. She has completed an MSci in Physics with a Master’s project on gravitational waves, but more recently has taken time to travel to pretty places, take up photography, and read old fantasy novels. Louisa is passionate about making science communication as enjoyable as possible for both the public and herself, and has adored astrophysics ever since she realised that staring into space could be a career.