The path to a revolutionary telescope

Dietrich Baade and the New Technology Telescope ‘Dream Team’

- How ESO’s New Technology Telescope paved the way for today’s large telescopes

- How astronomers and engineers dealt with the early challenges to operate such a unique and complex telescope

From its cradle in the Chilean desert, the New Technology Telescope (NTT) opened one eager eye onto the cosmos in March, 1989. Aided by a stunningly clear sky, the NTT’s first image, a shot of the globular cluster Omega Centauri, was of the best quality recorded in ground-based astronomy at the time.

Celebration followed for the NTT’s parent institute, the European Southern Observatory (ESO). Not only had the NTT successfully launched, but it had also proven the incredible potential of active optics, the namesake ‘new technology’ of the telescope.

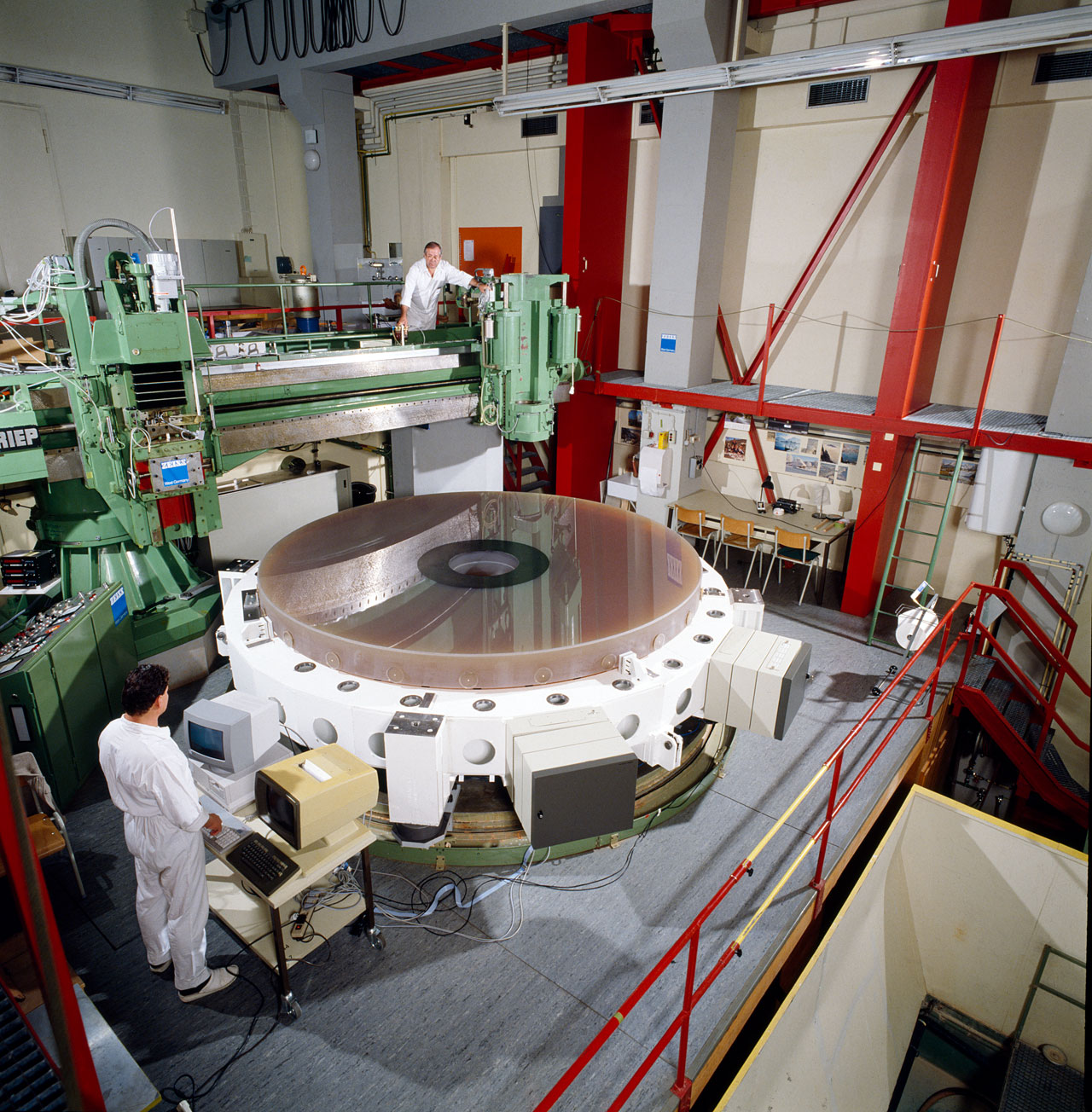

Active optics, conceptualised by Raymond Wilson, had been designed to counteract distortion of the telescope’s primary mirror from effects like gravity or temperature, which had meant previous telescope mirrors needed to be thick to avoid deforming, and small to minimise the effects. Active optics promised a new era of astronomical image quality and ever-larger telescopes. The NTT would be an enormous advancement for the astronomical community, but was also a proof of concept for ESO’s biggest project yet, due to take the stage in 1998: the Very Large Telescope (VLT).

But in the following years, as construction began on the VLT and expectations built, the astronomical community noticed that the NTT was not performing as it once had. “The new image quality that had been delivered at the time of commissioning was sensational,” says Dietrich Baade, a now-retired astronomer who worked with ESO since 1981. “But the NTT did not deliver its potential for superb images as often as users expected. It was not reliable.”

In the summer of 1993, with the clock ticking down to the inauguration of the VLT in only five years and negative headlines about the NTT starting to appear in the press, ESO’s Director General, Riccardo Giacconi, hosted an urgent meeting to address the issues. “He asked me whether I was willing to look at this,” says Dietrich. “I asked for time to think — but I had decided almost on the spot that this is something I would do.”

The NTT lives in the dry mountains of the Atacama Desert at La Silla Observatory, two hours drive from the nearest town. Dietrich had previously worked on-site.

“Once I went on a 4-day hike with a backpack and a tent. It had always been my dream to see what is on the other side of the mountain ridge east of La Silla. That tour gave me an impression of how isolated La Silla really was,” Dietrich remembers. “Under the lonely remains of what must have been a tree, I was observed by a beautiful metallic-green hummingbird, which encircled me at a distance just large enough that I could not have reached it. Contrails were the only trace of human life, in a completely detached other world.”

Operating a telescope on such an isolated site posed a challenge — especially with the technology of the time. “Telephone was a rare commodity. La Silla had, I think, two external telephone lines, and in the evening, people were lining up to talk with their families,” Dietrich says. “Communications in general at La Silla were extremely limited.”

Tasked with finding what issues might be plaguing the NTT, Dietrich first noticed a difference in perception between the staff based at ESO’s Garching headquarters who had designed the telescope, and those supporting its operation in La Silla.

“I talked to various people in Chile: they believed that [the NTT] just wasn't mature, right? Not surprisingly, in Garching, people thought that in Chile [the engineers] don't operate our wonderful product [correctly],” says Dietrich. “I concluded that the truth must be somewhere in between these two extremes. When astronomers who [visited La Silla and used the NTT] had a problem, they called the operations group, [who] were in charge of all telescopes and instruments at La Silla.” Being called at random when they happened to be on the mountain on weekly shifts meant the team ”could not develop the expertise in the NTT that such a complex and all-new facility demanded.”

Alongside support difficulties, the NTT was also experiencing growing pains. The software operating the NTT was a unique development, making it hard to train new staff or astronomers. Even mechanically, while tracking objects in the sky, there were problems. “The azimuth bearings got stuck from time to time. People would come with a rope, and two or three very physically strong, heavy men had to pull the telescope and that made it work again,” says Dietrich. “Sounds very old fashioned, and not really in line with the aspiration of a New Technology Telescope.”

Understanding that the operation of the telescope was key, Dietrich asked the Director General if he could put together a dedicated operations support team. “He gave me the possibility to select the people I wanted,” says Dietrich. “This is something I had never heard or seen before — it was a privilege. And it was a dream team.”

Dietrich formed mixed teams including astronomers, electronics engineers, and software engineers, working in shifts to support the NTT. “That was a wonderful thing because software and electronics respect each other; they don't compete. In a mono-disciplinary group, you have competition. And where there is competition, there is friction. These two had only one goal: to make the telescope perform as best as possible.”

Building a bridge between astronomers and engineers would also be vital. “My aim was that everyone in the NTT Team had an overview of the end-to-end functioning of the NTT. Only astronomers can contribute the original scientific goals and the ultimate outcome. Therefore, I seized every possible opportunity to explain [to] the engineers how their work relates to the scientific use of the NTT,” says Dietrich. “I always found that if an astronomer explains why something is important, [engineers] appreciate this, because it enables them to deliver the best possible technical performance in pursuit of scientific goals.”

As well as being on-call for astronomers who needed support, the NTT team began to maintain the telescope, complete checks and reports on its state, and generally aimed to make it more reliable by understanding the function of all the major subsystems of the NTT. For Dietrich, leading the team would be a new experience — especially while staying based across the world, in Garching, whilst the support team operated in Chile.

“We were fortunate that this was the beginning of email, and with ESO’s diplo-bag service, [regular] mail took only 3-5 days to move between Chile and Garching.” Both of these communication channels made overseas interactions much more efficient. “Chile is four to six hours behind [depending on the season], so these were long days, late days, late hours for me. But perhaps it created, in Chile, a motivation. The team had a certain degree of autonomy, and were given a share of developmental work for the new NTT control system, which, for the engineers in La Silla, was a new experience that I think worked well.”

At ESO, the name ‘NTT Dream Team’ began to float among astronomers as operations ran increasingly smoothly. Outside of operations, the team were even able to fix the mechanical problems with the NTT’s altitude bearings. It was not a mechanical engineer, but Domingo Gojak, an electronics engineer, who found the solution.

Domingo had realised that the ball bearings within the NTT were typically used in machines that would fully rotate, millions of times. But the NTT pointed up, and down, and then up again, without ever making a full rotation, allowing the balls to settle at the bottom of the bearing and block the motion of the telescope. “That is, in my opinion, teamwork at its best: that team members also have the courage and the capability to make contributions outside their immediate competence,” says Dietrich. “That was wonderful.”

Meanwhile, in the astronomical community, the NTT had gained traction as an optical telescope of unrivalled quality. The NTT detected galaxies at the furthest reaches yet, revealed the first pulsar in another galaxy, and saw stars swirling at the centre of the Milky Way, paving the way to prove the existence of a supermassive black hole at the centre of our galaxy, a discovery that would one day win a Nobel Prize.

However, larger issues with both the hardware and software governing the NTT persisted. The system could not be upgraded easily, and, being one-of-a-kind, it remained difficult to train new staff or astronomers to use. These issues were beyond the scope of even the Dream Team. Joe Schwarz, an advisor on software matters to Riccardo Giacconi (ESO’s Director General at the time) suggested replacing the control hardware and software with that of the upcoming VLT, effectively using the NTT as a testbed for the VLT control system. This, however, would mean removing the astronomical juggernaut from service for almost a year.

“Giving up the supposedly most advanced ground-based optical telescope for a full year was not something that the community embraced,” Dietrich recalls. Some research requires observing objects over a long period of time — for example, stars orbiting close to a black hole — and having such a significant pause in the middle could have disrupted these measurements. “But the community bought into the argument that the productivity of the VLT and its four 8-m telescopes would more than compensate for this one-year loss of a single 4-m telescope.” Ultimately, the plan went ahead.

Around this time, Dietrich passed leadership of the NTT upgrade onto the astronomer Jason Spyromilio in order to make a return to astronomy, and tackle new functional tasks. The project, designed by Anders Wallander — the NTT Upgrade Project Engineer and Manager — consisted of many test periods lasting a few nights. Each test was dedicated to only a single component of the control system at a time, and culminated with a ‘Big Bang’.

This massive final hurdle affected many systems of the telescope, both hardware and software, but was ultimately successful: in July 1997, under skies as remarkable and rare as the day the telescope had seen first light, the NTT awoke.

“Measurements revealed that the seeing at La Silla had substantially degraded since first light in 1989 — just to recover at the beginning of the NTT Upgrade Project. We had the opportunity to show our skills under these wonderful external conditions,” says Dietrich. “We can only be grateful for it.”

In August 1997, the NTT underwent a meticulous review and was found to be in excellent condition, and it was hence welcomed officially back into the ranks of La Silla. The NTT has been unstoppable since then. Nowadays, even as the VLT is well-established and ESO’s next big project — the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) — is underway, the NTT is still a beloved contributor to astrophysical research.

Dietrich believes the success of the NTT Upgrade should be attributed to the devotion of the team that worked on it. “It was delivered reliably because of the hard work of the NTT team. I've always been fortunate that I could work with very capable, motivated teams. It's teamwork — it's not the individual that counts,” says Dietrich. “That makes work at ESO so rewarding.”

“The other day I was talking with a friend of mine working in the industry, [and he said], ‘One thing I noticed is, when you talk about ESO, you say we.’ And yes, that makes a big difference, because it means that people buy into what they do.”

Now retired, Dietrich is still at the heart of the ESO community, contributing to astrophysical research, mentoring students, and being a valued (if troublesome) member of ESO’s Board Game group.

“If you’re wondering why I stayed with ESO all these years: it’s because I never found anything better.”

Links

- The development of active optics – article in ESO’s The Messenger journal

- First images from the NTT – short film from 1990 showcasing some images from the telescope's first light

Biography Louisa Spillman

Louisa is originally from a small countryside town in England. She has completed an MSci in Physics with a Master’s project on gravitational waves, but more recently has taken time to travel to pretty places, take up photography, and read old fantasy novels. Louisa is passionate about making science communication as enjoyable as possible for both the public and herself, and has adored astrophysics ever since she realised that staring into space could be a career.